The fate of Princes in the Tower is one of the most intriguing mysteries in British history, steeped as it is in heavy emotive imagery. It immediately summons the visual of two small, fair haired boys, clinging together for comfort; lambs kept for the slaughter by their dastardly uncle. And of course, thanks to Shakespeare, our image of Richard III for years was similarly melodramatic – the scheming, malevolent hunchback.

Thanks to such sensationalised fiction, and the countless artistic interpretations of later painters, it’s become embroiled in the national consciousness as an open and shut case – with Richard determinedly accepted as the villain. The Richard III society naturally does much to combat this, but occasionally works at a disadvantage. There remains a common theme amongst a lot of the historical community that, whenever a remotely pro-Richard theory raises its head, the response is a rather condescending eye roll and a comment to the effect that “Those loony Ricardians are at it again!” , clutching at any available straw in an attempt to rehabilitate their hero.

Of course, historical study by its very nature is subjective; rarely is it possible to look back on a period and not have at least a little feeling about who is in the right and who is not. Consequently, we are either – to trivialise the matter – Team Richard or Team Henry; believing that one or the other is the mastermind behind the Princes’ untimely end.

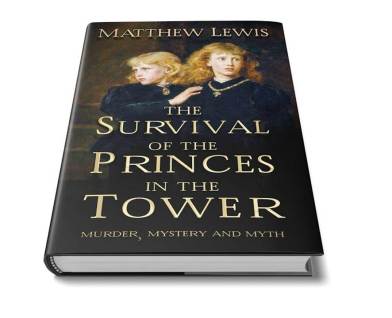

Less common is the school of thought that the young Edward and Richard survived, and this is the subject of The Survival of the Princes in the Tower by Matthew Lewis. It has been an absolutely fantastic read! I’d hoped to get through it quicker but work has dictated otherwise. I was able to get properly into it this weekend though, and I really couldn’t put it down.

I thoroughly recommend it for anyone with an interest in the period, whether you are Ricardian or otherwise. It is so well-written that if it doesn’t take your preconceptions and shake them up a little, I would be very much surprised!

Central to Lewis’s work is the fact that – although so many seem to take the murder of the Princes as a certainty – there is in fact no real factual contemporary evidence to suggest that this actually did happen. There is too much that doesn’t add up… and too much information that only appeared when it was convenient to the Tudor dynasty.

What I love most about this book is that every theory, every inference, every argument is based on logic; which very much appeals to my inner Spock. If solving a modern crime case, we would take it as read that the detectives/forensic scientists/criminologists would rely on much more than hearsay and emotive triggers; but this is an approach that is often abandoned when it comes to looking back on historical cases.

Lewis, however, has produced an absolute masterclass in objectivity, with every chapter written in a perfectly balanced style free of bias. He paints neither Richard nor Henry as saint or sinner. Every separate theory is weighed up for plausibility, and the factors working both for and against it are discussed at length.

He posits the idea that, far from perishing as children in the tower, the princes may actually have survived to adulthood, citing the lack of factual evidence in favour of their deaths. He discusses what he calls the Black Hole Effect of the princes; examining the behaviour of various contemporaries in a way which suggests a gravitational pull around some unknown force – which could only be their survival.

The book discusses several key theories:

1. Richard III arranged for both princes to be taken from the tower and made provision for their safety.

Lewis addresses the major problems with the ‘mean old Uncle Richard’ theory very early in the book, though he does not dismiss outright he possibility that Richard may indeed have been the culprit.

He discusses the numerous problems with it: firstly, the fact that acting in this way would be a sudden departure from a lifetime of honourable behaviour for Richard III. He also raises the point that Richard had nothing to gain from carrying out the murder and keeping it secret; if he had done the deed, he could have found a convenient scapegoat in the Duke of Buckingham. Coupled with this is the fact that Elizabeth Woodville allowed her daughters to come out of sanctuary to attend Richard’s court – not particularly likely should she believe her sons to be dead at his hand!

The first part of the book identifies numerous pieces of evidence which suggest, although certainly do not confirm beyond doubt that Princes survived, certainly give the reader plenty to think about.

2. Edward V led the first rebellion in 1487 and may have died at the battle of Stoke.

Lewis picks apart the Lambert Simnel story with great insight, pointing out all the ways in which it fails to ring true. The jarring, unusual name may have been coined by Henry VII as a way of setting a pattern for future ‘pretenders’ and when considered impartially, this does make sense.

Lewis suggests that, far from being a peasant with delusions of grandeur, this invasion may have in fact been led by the young Edward V in an attempt to reclaim his kingdom. The points working in favour of this argument are: the support of Margaret of Burgundy, the Earl of Lincoln (who himself had a claim to the throne) and the Irish lords, as well as the involvement of Lord Lovell. He also points out that those same Irish lords failed to recognised Lambert Simnel when the same alleged boy served them wine a few years later, suggesting that this boy was a creation of Henry VII.

This was a really well constructed argument that I’d never studied in depth before, and certainly made me think. Of course, if Edward V really did die in battle, there goes any chance of ever finding his body!

3. Perkin Warbeck was indeed Richard Duke of York.

Here Lewis brings up the vast amount of logical evidence that work in favour of the second ‘pretender’ being a genuine son of Edward IV; his perfect English, intimate knowledge of Edward IV’s court, his insistence that he had three marks which could positively confirm his identity and his ability to charm the heads of several European states, some of whom supported him even when there was nothing to gain from doing so.

Henry VII is at his most Trump-like here; full of bluster and disingenuousness. If Warbeck was really an imposter, Lewis points out, then why not play his key card and have his wife, the boy’s sister, denounce him publicly? And why also the insistence on having him beaten so badly that his features could not be recognised in London?

This for me is one of the strongest and most convincing arguments in favour of the Princes’ survival.

4. The Princes were hidden in plain sight at the Tudor Court

I found this an absolutely fascinating chapter. I studied semiotics as part of my degree, so the deconstruction of the More family portrait by Holbein really appealed to me. It suggested that the painting was teeming with clues which announced that Edward V and his brother were in fact alive and well at the heart Tudor England all along, living under assumed names.

Although I’m not sure that I’m totally convinced by this argument, it did flag up some startling discrepancies about the lives of the two men who may have been the princes in disguise. If true, it would mean that in at least one case there was a clear line of descendants whose remains could possibly be used to establish DNA linkages.

This is only a very quick and superficial summary of the book’s contents, but I found it to be a series of extremely well-reasoned and well-written arguments. That every single one was presented with a total lack of bias, based wholly on logic, sets it apart from so many other works on this time period.

After reading it, coupled with a talk I went to from the Richard III Society last month about Perkin Warbeck, I’ve got to say I’m pretty convinced that the Princes in the Tower survived somehow. What Lewis terms the ‘Black Hole Effect’ is just too persuasive.

If you’re even remotely interested in the mystery, or in the time period in general , I urge you to go get hold of this book. It’s absolutely fantastic!

My rating 5/5.

Reblogged this on Matt's History Blog and commented:

A fantastic review of The Survival of the Princes in the Tower from Rachael’s Ramblings – I couldn’t have written a nicer one myself!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great review!

I’m sharing it on my twitfeed this week. 🙂

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Jo's Historic Collection and commented:

Did the princes survive?

LikeLike

A very nice review which made me want to read this book. But why bring up Donald Trump in it? Totally don’t get it.

LikeLike

I felt there were strong comparisons in Henry’s behaviour with the modern era. He made some very determined, blustering claims but then brought forward no proof. He would then say one thing and do another.

LikeLike

I wouldn’t say that people who believe that the boys were murdered tend to fall into the camps of blaming Richard or Henry. Buckingham has always been one of the main suspects and believed by quite a few people to have been the culprit (even back in the 15th century), which is one of the more credible theories, considering the fact he had both the greatest opportunity (being not just the 2nd most powerful man in the kingdom but also physically present in London and therefore basically in charge of the princes’ safety in the summer of 1483, when Richard was away from the capital) and pretty strong motives, considering his sudden switch of loyalties and participation in the rebellion/alliance with Henry Tudor and influence of John Morton, coupled with his own claim to the throne. Also, the people who believe the murder to have been done to make the way for Henry to gain the throne these days tend to believe the mastermind of it was Henry’s mother Margaret Beaufort – possibly in collusion with other people that were present in England at the time (like her husband Stanley, Morton, and/or Buckingham). The theory that Henry was the murderer seems to have been very popular for a while – during the 19th century and the first part of the 20th (including Josephine Tey’s Daughter of Time), but seems to have had a big decline in popularity, as most people tend to think that, if the princes were murdered, it had to happen during the summer of 1483, and that, if they survived, they were not in the Tower after that period. The belief that Henry was never sure what happened to them is also widespread.

I’ve seen all the theories mentioned here. I really don’t know whether the boys were murdered or survived. But there’s another option, which I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone put forward. There is far more evidence of Richard having survived than his elder brother Edward V. What if Edward was indeed murdered, but Richard was kidnapped/whisked away? Assuming “Perkin” was really Richard, that would line up with his account of being taken from the Tower by a nobleman and shipped off, and being told his brother was dead. Edward and Richard are constantly treated as a single unit in the popular consciousness, but in fact, they were 3 years apart in age and hadn’t even grown up together. (Which makes the melodramatic paintings of two boys who look like twins, clutching at each other and sleeping in the same bed, even more absurd. Which 12 year old would ever act like that with their 9 year old sibling? They’d see the younger sibling is a child compared to them. Add to that that the two of them barely even knew each other.) They had drastically different upbringing, and, according to contemporary accounts, different personalities. Edward had grown up in a separate household in Ludlow, Wales, as per custom for crown princes, under the supervision of his maternal uncle, Anthony Rivers. We can assume that he was a lot closer to Rivers than to anyone else in his family – he would barely have seen his parents and other siblings, and uncle Richard would have been a virtual stranger to him. Edward was also described as the more melancholy one, at least in terms of his behavior when in London, as opposed to Richard, who the account seem to describe as more lighthearted. It’s very likely that Edward would have been seen as the more difficult to handle, being older and probably holding mistrust in Richard as well as Buckingham from the moment they captured Rivers, and that would have only grown after the executions of Rivers and Grey. If Buckingham was indeed the culprit, this theory would start making sense. What if he decided to dispose of Edward – who would be likely to hate him as much as he probably hated Richard III – but keep Richard, who was younger and presumably easier to manipulate, as a bargaining chip he could use against both Richard and especially Henry, but also possibly install as King so he could be his Lord Protector? Portraying himself a s the boy’s savior to gain his trust would have also been a good step.

Finally, this theory would also explain why the survival of Richard – “Perkin” – remained unknown and why no one tried to use him for their benefit or get rid of him until he grew up. If it was a part of Buckingham’s plan, then he died before he got to set it into motion. It also would be a fascinating answer to the question “What did Buckingham want to talk to Richard about when he was begging him for an audience before his execution?”

What do you think about my theory? I don’t think that’s necessarily what happened, there are several credible existing theories, but I don’t think anyone has proposed this one before.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think this is also a credible idea, and you’re right – it could definitely be a possibility that Buckingham had some genuine important information to impart before he died. Oh for a time machine to allow us to go back and find out what really happened! I don’t know if you’re a member of the Richard III Society, but a couple of members have done some very interesting research into Perkin Warbeck truly being Richard.

LikeLiked by 1 person